King tides offer look at the coast’s flooded future with sea-level rise

As dramatic as king tides can be when they flood the streets of Seal Beach or the Peninsula in Long Beach, an aerial perspective of waves battering the coast takes the drama to another level.

From 1000 feet above, you can see surf pounding long sequences of seawalls and riprap rocks protecting homes, the ocean sometimes appearing to threaten structures despite the installed barriers.

Where there are cliffs with no homes, the waves gnaw away at the bluffs, moving the beaches at their base farther inland.

The extreme king tides of the past few days occur only once or twice a year, but they offer a glimpse of what normal tides will be eventually be doing daily as the result of rising sea levels.

“It’s really a challenge because it’s a slow-motion disaster,” said Chad Nelsen, Surfrider Foundation CEO, during a coastal Orange County tour with two journalists aboard a single-propeller Cessna on Tuesday.

While the public has yet to raise a clamor over repercussions that will be felt increasingly in the decades to come, policy makers have begun adaptation strategies. With the California Coastal Commission in the lead, local jurisdictions are working on plans to variously accommodate sea-level rise and defend against it.

“We’re on the right track,” said Nelsen, a Laguna Beach native. “But there are really tough decisions to be made and that’s what’s to be determined.”

Limiting new seawalls

The three basic strategies for responding to sea-level rise:

- Transporting more sand to the beach.

- Building seawalls in front of structures and around islands.

- Allowing the ocean to creep landward and causing development to retreat to higher land.

In 2017, the city of Newport Beach approved spending up to $2 million to raise seawalls by 9 inches on Balboa Island, which at times is below sea level.

But when it comes to new seawalls protecting individual structures, the Coastal Commission has indicated its preference for giving the ocean the right of way.

Commission policy is to only approve seawall protection for homes built before 1977, when the Coastal Act took effect, and not if the property was subsequently redeveloped, according to agency spokeswoman Noaki Schwartz.

After a Laguna Beach homeowner rebuilt a seawall and performed an extensive renovation to their seafront home without a Coastal Commission permit, the commission responded last year with a $1 million fine and ordered the wall torn down. The issue is in litigation.

Surfrider is among those pushing for a stronger emphasis on what is dubbed “managed retreat.”

Nelsen says it’s inevitable that the ocean will eventually overtake some buildings on the coast and that should be planned for ahead of time.

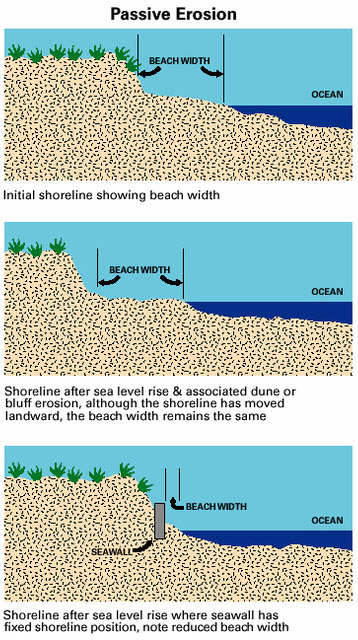

Additionally, allowing the ocean to migrate inland preserves beaches, he said.

While flying over Capistrano Beach in south Orange County, waves pounded the seawalls and sandbags protecting a long stretch of homes immediately behind the barriers.

In Laguna Beach, several beaches were interrupted by seawalls protecting homes virtually on the water.

“If those homes and seawalls weren’t there, the coast would migrate naturally and there would be beaches,” Nelsen said. “It’s erosion that creates the beach.

“In the long run, (managed retreat) is really the solution if you want to preserve beaches and marine life. Let’s face the reality that if we armor it, we’re going to lose public beaches and wildlife habitat.

“Should the private homes in the front row get to protect their homes at the cost of the public’s use and at the cost of ecology?”

Measuring rising seas

Environmentalists — as well as the Coastal Commission — are eager to raise awareness of sea-level rise.

The commission coordinated dozens of king-tide tours by local groups up and down the coast, and has a webpage featuring public-submitted photos documenting the dramatic surges.

Even the Surfrider aerial tour came as a donation — from LightHawk, a conservation group that recruits volunteer pilots and their planes to increase ecological understanding.

The king tides, which occur when the moon and sun are aligned with the earth and are particularly close to the earth, not only provided the opportunity to see what normal tides will look like in the future but also indicate which coastal areas will be most vulnerable.

While there are skeptics when it comes to sea-level rise, they are fewer than those who question man’s contribution to climate change.

“The sea level is rising,” Nelsen said. “We have tide gauges. It’s an observable phenomenon.”

And it’s accelerating, according to studies.

After rising 5.5 inches from 1900 to 2000 — an average of 0.055 inches per year — it is now rising nearly 0.13 inches per year, according to NASA.

Projections show that the seas will continue to rise faster and faster for decades to come regardless of human activities.

California’s Ocean Protection Council projections released in 2017 listed sea-level rise on the state’s coast ranging from 0.3 feet to 1 foot by 2030, 0.6 feet to 2.7 feet by 2050 and 1 foot to 10.2 feet by 2100, depending on a variety of variables.

Others put the rise at the high end of the Ocean Protection Council projections.

The city of Long Beach, using National Research Council data from 2012, has modeled future flooding based on an 11-inch rise by 2030, a 24-inch rise by 2050 and 66 inches by 2100.

Marine scientist Jerry Schubel, CEO of the Aquarium of the Pacific, told attendees of a Long Beach sea-level rise discussion this month the increase could be 7 feet to 10 feet by the end of the century.

He is among those who say some coastal neighborhoods will have little choice than to eventually abandon their homes.

Long-term planning

Sea-level rise is an effect of climate change, with expanding seas resulting from warmer water and melting ice caps and glaciers, according to studies.

While Surfrider shares the view that man is the primary cause of climate change and supports carbon reduction initiatives, Nelsen said that sea-level rise needs its own adaptation strategy because any reversal in carbon emissions won’t significantly reverse the rate of rising seas for more than 100 years.

Both Nelsen and the Coastal Commission emphasize the need for a long-term strategy, although they occasionally disagree on short-terms steps until that strategy is completed.

Last winter, the Coastal Commission approved an emergency permit to install riprap on the road to the parking lot at San Onofre State Beach, after the road partially collapsed because of high surf and tides.

One of Surfrider’s primary missions is to preserve surf spots, but that didn’t extend to waterfront parking in this case. Nelsen said his group opposed the emergency fix even though closing the beach lot would mean parking at the top of the cliff and hiking down.

Because the ocean is already moving toward the parking area, surfers and others headed to that beach might want to digest the prospect of clifftop parking, he said.

“That’s going to happen eventually,” he said. “Let’s come up with a plan. It’s a lot easier when you’re not in a crisis mode.”

The Coastal Commission’s Schwartz said that’s exactly what’s happening.

“State Parks has submitted their application for their long-term management plan for San Onofre/Surf Beach, which we will be bringing to the Commission for action the first half of 2019,” she said via email.